You hear complaints about the Callery pear, often called the Bradford pear, its most common cultivar. Why do so many people hate this tree?

There are some obvious reasons, like its weak wood, which breaks off in storms to damage fences, cars, and other property. Many people also find its floral odor offensive. But there’s a more insidious reason.

The Bradford pear cultivar is self-sterile (meaning Bradford pears can’t produce offspring with other Bradford pears). However, they readily cross-pollinate with other Callery pear cultivars that were introduced to replace the Bradford’s susceptibility to storm damage. Few insects eat Callery pears, but birds and other animals will eat their fruits. This spreads Callery pear seeds far and wide, which the Callery pear doesn’t mind since it can grow in a wide variety of environments. And they grow quickly, reaching maturity in as few as three years, at which point they start producing more of themselves. Calleries also don’t mind crowding, happy to grow in thickets that block out anything else from sprouting. Since they leaf out earlier in the spring that native trees, they quickly shade out native plants beneath them. And unlike their parent cultivars, hybrid Callery pear offspring tend to have 2- to 4-inch thorns (technically, spur shoots) that are sharp enough to puncture the tires of tractors, bush hogs, and other mowers. Here, I’ll show you a picture from my yard:

Ouch! And this isn’t even the hybrid Callery pear in our backyard. It’s from the Bradford pear in our front yard. Bradford pears normally don’t have these thorns, but we accidentally damaged the base of the trunk a couple of years back, and the tree responded by sending forth these spiky monstrosities.

Why would it do this? Well, trees are sometimes grafted onto rootstock of a different variety. One reason growers do this is to combine different traits into a single tree (like strong roots combined with desirable flowers). It turns out that our Bradford pear’s root stock comes from the type of Callery pear that HAS thorns. You’d never guess our otherwise attractive Bradford has this dark side just waiting to come up, but there it is.

That brings us to another interesting contrast between most trees and the Callery pear.

Here’s how most trees respond when you cut them down, or burn them with fire, or mow them, or strip a ring of bark from around their trunks:

They die.

Here’s how the Callery pear responds:

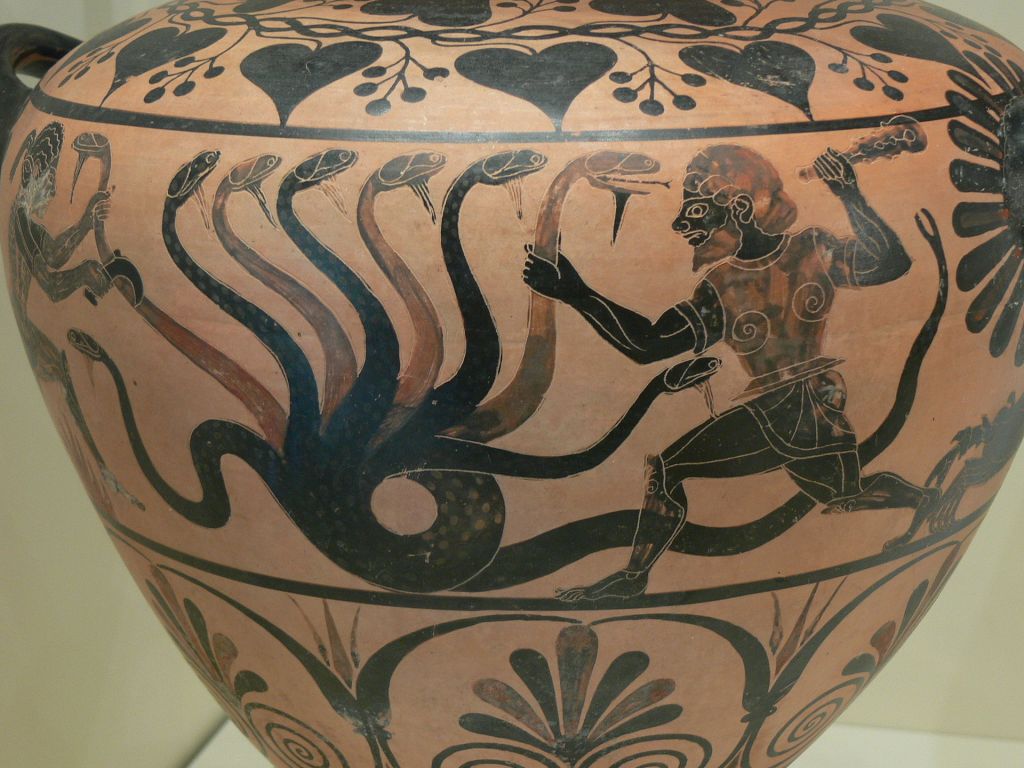

Like the mythical hydra, Callery pears come back with more sprouts than before unless you apply a potent herbicide. I mean, look at what happened when we nicked our tree. One freaking time. (Geez, tree, we said we were SORRY!) If you do enough damage to your pear tree, you can play a war of attrition by constantly cutting back at new shoots, but be prepared for many battles.

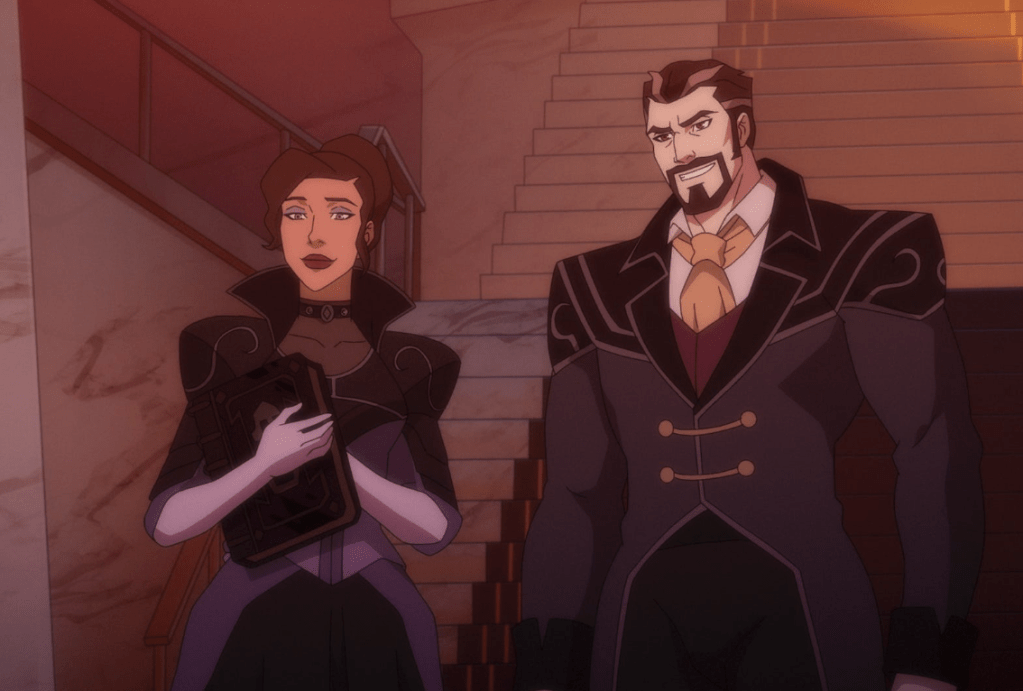

Bradford pears are the tree equivalent of the Briarwoods. They may look elegant, but they’re extremely hard to kill, they love displacing the natives, and they use all sorts of nasty tricks to stay in power and pursue their dark agenda.

Similarly, Callery pears are attractive, they rapidly overthrow the natives by stealing energy from them, they use other creatures to advance their power, they occasionally smell like death, and they never seem to die.

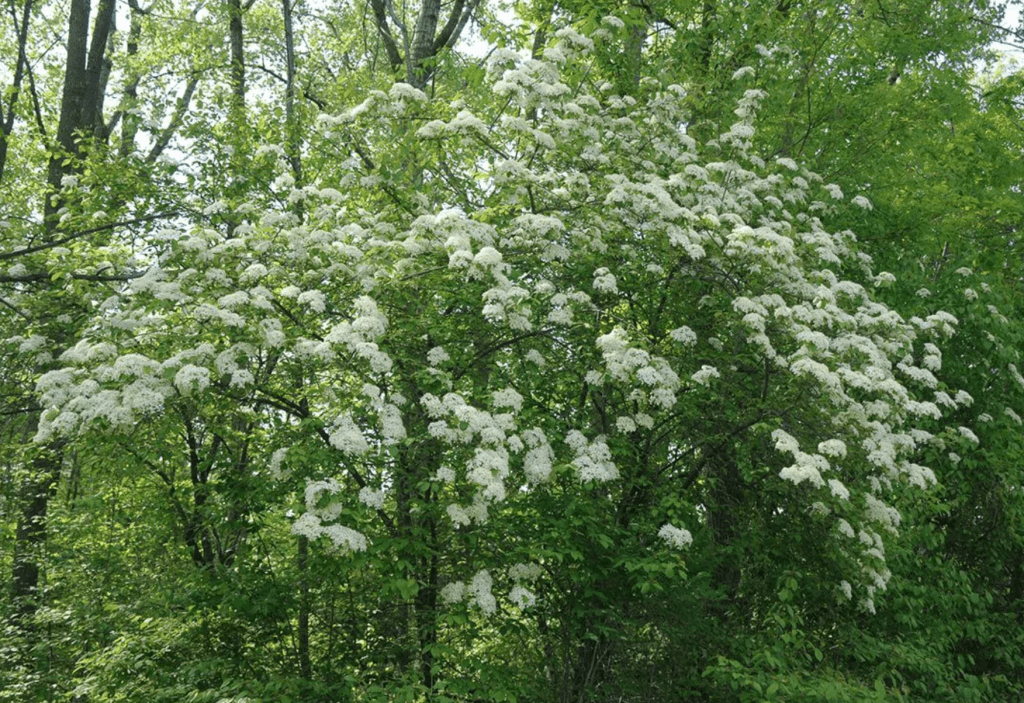

The featured picture for this post (at top) shows a relatively young thicket of Callery pears just down the road from me. You can see how they dominate the scene. Native plants can’t sprout or grow in this kind of environment because they’ve been shaded out by Callery pears.

Well, wait, we might say. What about survival of the fittest? If the Callery pear is so dang good at growing here, maybe we should just let it do its thing.

That argument might make sense if the Callery pear were the only new species introduced to the Americas in the last thousand years or so. And it might make more sense if we hadn’t unwittingly planted thousands and thousands of these trees all over the place in a tiny timeframe (geologically speaking). The problem is that humans have introduced thousands of species in the last 200 years alone, and we’ve planted various cultivars of the Callery pear all over the place. It’s not that our native species are weak. (For example, our native black cherry is highly invasive in Europe because the bacteria keeping it in check here isn’t found there). It’s that invasive species like the Callery pear have a serious unfair advantage.

Also, as I mentioned above, almost no insects eat the Callery pear in North America. Why would we care about this?

Even if you happen to hate insects, insects make up a HUGE portion of the food chain. Insects serve as food for other insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals large and small. If Callery pears don’t support insects, they’re a waste of space, nutritionally. This problem quickly compounds over time as Callery pears (and other invasive species) replace more and more native habitat. As they do so, they provide little nutrition while quickly filling the environment with more and more junk. Empty Calleries, indeed.

So what do we plant instead?

If you happen to like a low-growing tree with white blooms in spring, consider the following native plants:

American Fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus)

A smaller tree, growing from 12 to 20 feet tall and wide, it has multiple stems, but you can train it into a single trunk. It has fleecy, white flowers that bloom later in spring but look fantastic.

Carolina Silverbell (Halesia carolina)

The Carolina silverbell can grow 30-40 feet tall, though it may need to be pruned if you’re going for a specimen tree shape. It boasts bell-shaped flowers in spring.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier species)

This is a great small tree (or large shrub) if you’re looking for something edible! The white flowers give way to berries that ripen in June (hence the other common name of “Juneberry” for this plant).

Viburnum species

More of a shrub than an outright tree, some viburnum can be pruned to a tree shape. Many native viburnums have white flowers, but other colors are available. We dug out the Callery pear in the backyard and replaced it with a Blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), which is a high-value wildlife plant in our area.

Here’s the before-and-after, in case you’re curious:

Before: Callery pear, thorns and all

After: Blackhaw viburnum

Now I just need to muster the courage to take on the giant tree in the front yard…

Leave a comment